Mergers and acquisitions are often viewed with some reservation among public shareholders. After all, most acquisitions fail to create value for the buying shareholders, especially on a per-share basis. In hindsight, the prices paid and the synergies calculated seldom make any sense, and thus only the acquired company, plus the bankers, stand to gain. These base rates related to M&A are also deeply ingrained in most finance alumni sifting the world for investment ideas. Perhaps this could represent some type of opportunity?

The Map is Not the Territory

What if you could partner with a group of world-class capital allocators, sticking to a proven M&A playbook in private markets and sidecar their compounding trajectory of high-return investments? Private equity? No, these publicly listed companies have permanent capital, liquidity, diversification, and zero fees.

What I’m referring to, more specifically, are high-performing conglomerates, possessing investing superpowers at the helm, running decentralized operations in fragmented end-markets, and allowing for organic and inorganic growth via multiple small private investments. These are diversified and self-funded entities. Hence acquisitive growth is more akin to organic growth and is not reliant on capital markets. To be clear, we are not dealing with roll-ups or turnarounds and, indeed, not “transformative” acquisitions in public markets with integrations and lofty synergy targets.

These companies are capital allocation vehicles at their core, targeting smaller-sized private businesses with a data-driven acquisition process. They provide a reinvestment engine where organic reinvestment opportunities are often lacking. Essentially, they are bridging the gap between the capital allocation layer at the top while releasing entrepreneurial spirit and autonomy throughout the group, adding diversity, resilience, and scale, derisking the overall base.

The programmatic approach mentioned is critical. I first stumbled upon a McKinsey report in Demesne Investment’s “Practice Makes Perfect” article. According to their account on How lots of small M&A deals add up to significant value: between 2007 and 2017, the programmatic acquirers in a data set of 1,000 global companies achieved higher excess total shareholder returns than did industry peers using other M&A strategies (large deals, selective acquisitions, or organic growth). The study also highlights the importance of building organizational infrastructures and establishing best practices across all stages of the M&A process—from strategy and sourcing to due diligence and integration planning to develop the operating model.

The main takeaway from the McKinsey study highlights the importance of practice and frequency:

By building a dedicated M&A function, codifying learnings from past deals, and taking an end-to-end perspective on transactions, businesses can emulate the success of programmatic acquirers—becoming as capable in M&A as they are in sales, R&D, and other disciplines that create outperformance relative to competitors.

It follows, then, that the base rates on M&A are primarily anchored on large-deal public M&A and not the particular group of programmatic acquirers chasing multiple small private investments. The frequency of smaller deals across verticals with similar themes builds repetition, competency, and shared best practices within the group. This allows for better M&A processes on the HQ level and throughout the group with more people responsible for M&A, scaling deal volume. Shared best practices on working capital, pricing, and numerous other things help generate organic uplift, a vital contributor to overall growth, and something the best-in-class serial acquirers really excel at. The organic growth engine some of these companies possess is overlooked in my opinion and is something I will discuss in a separate blog post later.

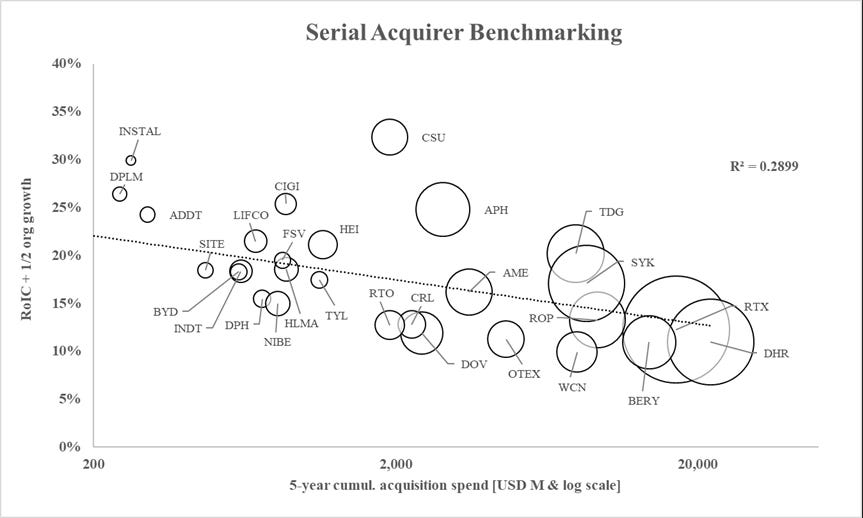

Again, great programmatic acquirers are laser-focused on scaling deal volume and steer clear of increasing deal size to avoid diminishing returns to M&A; after all, deploying large amounts of capital at high returns becomes increasingly complex, and bigger moaty businesses invite more competition and higher prices, lowering incremental returns. Even when ignoring turnarounds and integration, bigger transactions add more risk. Hence, a growing decentralized organization without decentralizing the M&A responsibility could eventually face diminishing returns as they age, as pointed out by Canuck Analysts in “Studying Serial Acquirers,” where they did some excellent benchmarking proving their point:

bubble size = amount of EBITDA, USD

X-axis = log scale of cumulative M&A spend over the past five years.

Y-axis = ROIC + 50% of organic revenue growth

You don’t need the help of the line of best fit in the chart to be able to tell that things go downhill as serial acquirers age and the amount of cash flow available for reinvestment gets larger.

At Danaher or Roper’s scale, it’s quite hard to bust out a double-digit long-term RoIC when your average deal size is 500M to a billion dollars with average EV/ EBITAs closing in on 20x.

That leads to the basic, but powerful law of diminishing returns to M&A:

As a) average deal sizes grow and b) the amount of annual cash flow that must be reinvested grows, incremental returns on capital decline.

The biggest roadblock to defying the law of diminishing returns to M&A is that most serial acquirers, particularly platforms and accumulators, do not sufficiently scale the human capital involved in M&A and the structures and processes guiding them – as they get larger. Inevitably, this lack of investment in human capital creates a bottleneck, leading them to scale by doing larger deals to move the needle rather than doing more deals. - Canuck Analysts

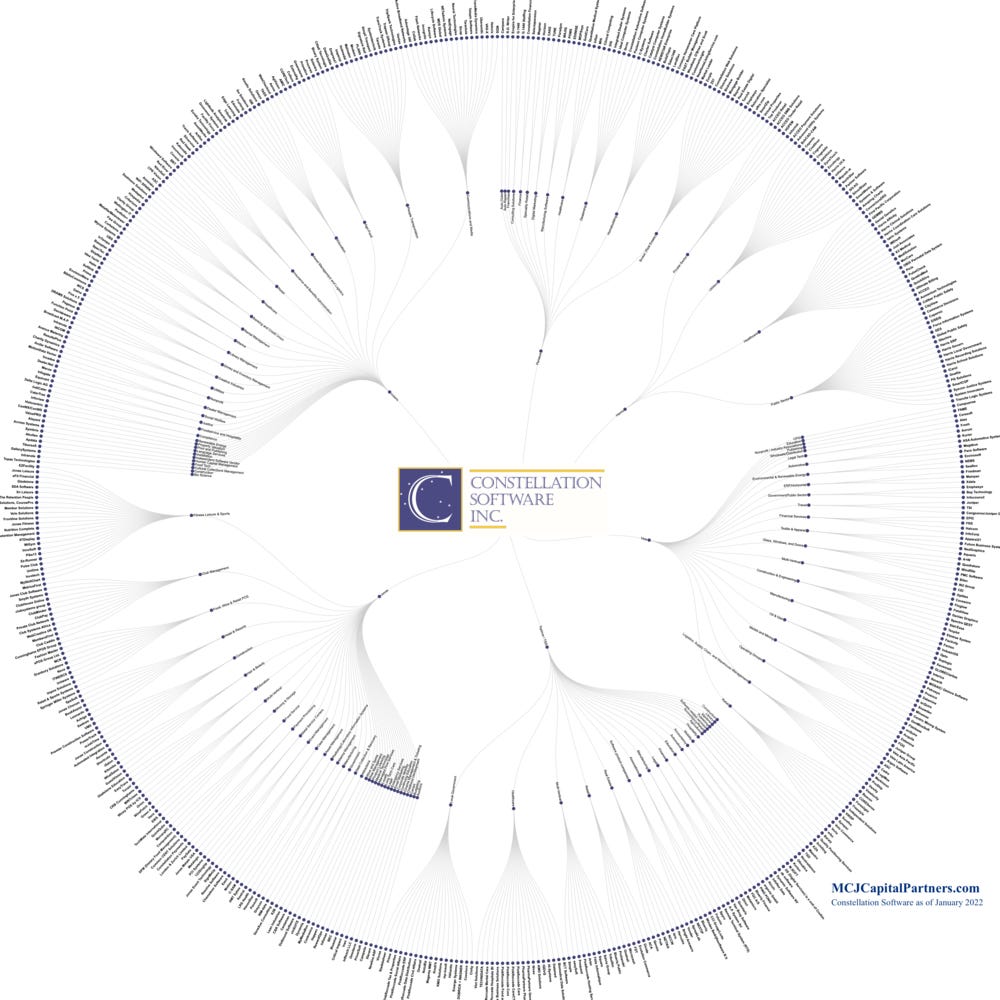

Speaking of smaller deal sizes, Constellation Software, a VMS-specialist acquirer at a $32 billion market cap and ~$5.5 billion of consolidated sales, is still targeting smaller companies, even after ~700 transactions since 2015 with a median acquisition size of $2.8 million. Constellation Software is organized through 6 operating groups (which do their own acquiring), diversified across 100+ different verticals and 1000+ underlying businesses running autonomously. Furthermore, each of the six operating groups serves specific verticals like agri, education, healthcare, real estate, construction, and hospitality. More importantly, even the underlying business units, which sit between the operating groups and individual companies, are incentivized to do deals up to certain thresholds without approval from the HQ.

Remember that most smaller private deals should warrant a hefty size/illiquidity discount compared to click-and-buy public markets; smaller businesses often depend on a few individuals and a limited number of customers and suppliers. Importantly, however, these are deals at sales thresholds more immune from interest by search funds and private equity. Furthermore, scale and reputation can also attract lower prices, typically achieved when deals are sourced internally over some time, where the seller either wants to stay on post-acquisition or see the benefits of becoming part of a more prominent company offering more resources.

Niching Down

Fertile hunting grounds for serial acquirers are narrow markets that attract and allow only a small number of specialists to dominate, providing sticky products or services that are mission-critical to the end customer but a tiny part of the cost they are protecting. The key is finding niched businesses at great prices that are somewhat shielded from the micro and macro volatility that most small businesses face.

Case in point, vertical market software (VMS) is deeply tailored for a specific industry in contrast to horizontal software like Microsoft Excel. Deep customization and its mission-critical attributes enable high switching costs (high retention), pricing power, recurring revenue, and often negative net working capital. VMS examples include software for traffic control, regulatory software for waste management, booking systems for golf clubs, church-related administration, software tailored for mortgage and real estate lending, and dental software (and much more). Recurring revenues with high margins and low capital levels are required to generate high recurring cash flows. However, a VMS business may not always provide the most significant organic reinvestment opportunities compared to horizontal software, which is perfect for serial acquirers providing a reinvestment engine but not so interesting for more considerable funds looking for scalable industries. Still, the attraction for great moaty VMS businesses is widely shared, but the market is growing all the time, with a VMS company like Constellation Software disclosing north of 40,000 targets, growing at a rate of 4,000 a year.

Niching down and focusing on market leaders create fertile ground for stable cashflows (albeit at higher prices compared to turnarounds), which organically funds more acquisitions at lower financial risk, often targeting low net-debt-to-EBIDTA ratios and low-risk deal structures. A side note on the importance of being self-funded, David Barber, co-founder and the retired CEO of Halma, once said that internally funded acquisitions are more akin to organic growth in contrast to those deals funded by share issues, which is an interesting statement (h/t Chris Mayer):

I would suggest that the first distinction to draw is between acquisitions funded by internally generated surplus cash and those funded by share issues. As l said earlier, in Halma, because of our high rate of return on capital, we have been able to support almost all our acquisitions from surplus cash....the first distinction l would draw is that growth by internally funded cash is more akin to organic growth than it is to grow by acquisition. - David Barber (Delivering Shareholder Value, 1997)

Trust But Verify

A decentralized structure prioritizing stable cashflows right from the start allows for more management resources spent on acquisitions, not micromanagement and integration. All these ingredients must be in place for successfully scaling the M&A machinery without friction. Easy in theory, very difficult in practice. Decentralization can also enable a bundle of other great qualities, from a podcast with Charlie Huggins on serial acquirer Diploma:

Decentralization works well when done right, because you retain the agility, autonomy, and entrepreneurialism as you grow in size. That's one of the great challenges for businesses is when they scale, they lose what it is that made them successful in the first place. I think Charlie Munger says bureaucracy is like cancer, avoid it like the plague. Most businesses get more bureaucratic as they get bigger, and they become vulnerable. Decentralized businesses tend not to because each company within the group is independent. They can scale themselves. The overall business can scale without these smaller businesses becoming that much bigger. So it just makes it easier to scale.

Doing it right, however, sometimes requires sacrificing apparent cost savings followed by a trust-but-verify approach, pointed out by Nick Howley, founder and long-time CEO of TransDigm:

I would say the decentralization was almost a religious belief for Doug and me. We both felt very strongly that if you want people to act like owners, you have to treat them like owners and pay them like owners and give them a fair amount of autonomy. That was just a very strong belief the two of us had. We also had experience in different large organizations.

One, you have to believe it because you have to pass up at times apparent cost savings on the belief that the loss of entrepreneurial spirit and ownership will more than overcome what you might save by having a common account receivable department or something like that, or a common sales force. You just have to believe that. You'll do a lot better if you lived it for a while and had to deal in a corporate environment, where it just stifled people like that. The other thing you got to do is you got to get rid of people fast that don't fit. Everyone says they want to be autonomous and run a decentralized business. The fact of the matter is what they mean is they want to be responsible when things are going well, but not responsible when things are... “I'm president of the good stuff.” No, you're president of all the stuff. You got to be quick to fire when somebody doesn't fit in culturally.

Cultivating a highly entrepreneurial culture in a decentralized structure, combined with investing superpowers is rare but extremely powerful. This way, conglomerate discounts can be turned into conglomerate premiums as long as you have simple profit goals, decentralization, and provide employees with trust, as noted by Gustaf Håkansson after interviewing Fredrik Karlsson from Röko (and prior CEO of Lifco for 20 years). I liked the way the author framed this:

Entrepreneurial drive coupled with a rational and tax-efficient internal capital market can warrant a conglomerate premium.

Much more could be said regarding great decentralized systems, and I particularly find trust-based business models to be mostly ignored and under-discussed by market participants. Why is that? Perhaps because the cumulative effects are only visible in more extended time frames?

Taxonomy of Serial Acquirers

There are already great taxonomy frameworks from Scott Management (Ryan Krafft), REQ Capital, and Demesne Investments. To keep it simple, I find it helpful to split acquirers into specialists and generalists. Specialists are comprised of roll-ups with a high degree of integration, rolling up a single vertical, often chasing synergies. Names that come to mind are United Rentals and Dental Corp. The second type of specialists are theme-based specialists like Diploma, Constellation Software, or Addtech, often honing in on specific niches or themes across multiple verticals, compounding domain knowledge like a rollup, but still flexible and opportunistic within their universe. Moreover, synergies are not forced but often welcome.

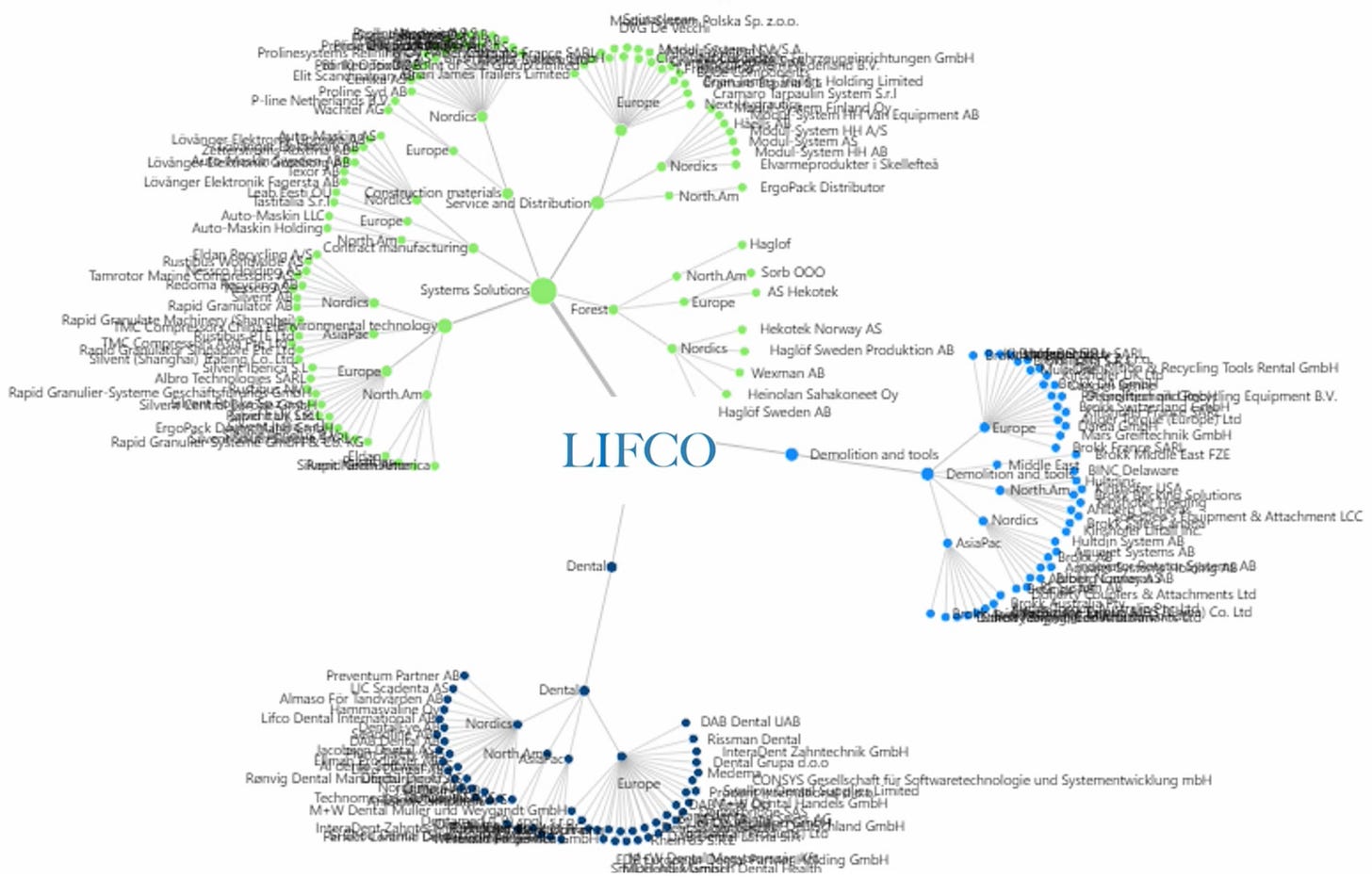

Generalists, on the other hand, may often appear to be focusing on specific niches, in practice, however, they buy everything across sectors, either in a decentralized structure (Lagercrantz, Lifco, Roper) or more centralized. To flesh out this a little bit more, a generalist acquirer like Lifco has three segments, one of them is called “system solutions,” where they put almost anything which does not belong in the other two boxes (dental and demolition & tools), and similarly with Lagercrantz and their “international” segment which serves the same purpose. The segment’s name becomes a residual of the investment, keeping maximum flexibility as they perpetually learn and move from one domain to a new one. They come in many shapes and colors, but this is the scaling approach for generalists I find most compelling. In my opinion, generalists and theme-based specialists, doing it right, resemble a great flexible IRR-focused investor and provide the most considerable diversification and scaling opportunity for investors.

There are other reasons I find generalists and theme-based specialists more attractive: roll-ups focusing on integration are often in a hurry chasing deals with specific short-term goals around future acquired sales and synergies, often without considering return on capital. While Lifco or Constellation Software often source their deals in-house and avoid broker-led auctions, roll-ups are often busy trying to meet sales guidance that incorporates future deals. The urgency might be real; after all, rolling up single vertical means TAM is limited, and new competition from PE might be imminent. However, urgency and short-termism create complexity, poor incentives, and sometimes lousy performance for shareholders. It`s a shift in mindset, and the strategy for most roll-ups doesn’t lend itself to great investing. There are many exceptions, and claiming roll-ups are wrong is the same as saying all M&A is bad. Still, I recall an interesting discussion by Brent Beshore on horizontal vs. vertical roll-up strategies, documenting the weird psychology that underlies these processes.

Durability and Root Systems

As investors, we are automatically drawn to fast-growing companies without considering the force multiplier of compounding, which is time. We tend to seek the obscure instead of the obvious, which means over-weighing the recent vivid evidence. Typical examples are ephemeral stuff like optical cheapness and quarterly EPS, while corporate attributes like longevity and durability permanently lose against our perceptual gravitation towards novelty.

On the surface, some acquirers may be perceived as relatively dull companies with boring organic growth prospects. Still, their ability to scale and reinvest a high portion of earnings year after year at good returns can lead to non-linear outcomes. Most of us are repeatedly surprised when we look at reverse DCFs for high-performance acquirers and realize we could have historically paid a very high start-multiple and still receive an excellent market return. The mathematical explanation, however, is first and foremost derived from the durability of returns and the time exponent.

Compounding is just a return to the power of time. Time is the exponent that does the heavy lifting, and the common denominator of almost all big fortunes isn’t returns; it’s endurance and longevity. “Excellent returns for a few years” is not nearly as powerful as “pretty good returns for a long time.” And few things can beat, “average returns sustained for a very long time.” - Morgan Housel

So, to fully achieve compounding magic, one must first arrive at the “second half of the chessboard”, a phrase by Ray Kurzweil about the point where an exponentially growing factor begins to have a significant economic impact. To arrive there, however, means minimizing interruption and not blowing up in the meantime, both at the business and investor level. After all, if you keep running the clock on a low-probability event, it`s bound to happen. This applies not only to nuclear circumstances but also to business-model risk. This is why the best acquirers should be celebrated for their compounding superpowers and equally applauded for becoming more internally diversified, adding resilience, adaptability, and scale, derisking the enterprise.

Combined ingredients increase the odds of arriving at the second half of the chessboard, where compounding essentially gobbles up everything. And as we know, stock prices eventually mirror intrinsic value growth.

A helpful mental model for diversified and self-funded acquirers is thinking about the root systems of plants and trees (h/t to LibertyRPF). Some companies may have a single but shallow root, represented by a single product sold to a single customer in a single end-market. A fragile three-legged stool in most scenarios!

Alternatively, one could own a decentralized Holdco with great capital allocators at the top, releasing entrepreneurial spirit at the business level across multiple end-markets, both in terms of verticals and geographies, smoothing out cyclicality. We’re looking for a root system sprawling in all directions and over great distances; they are much harder to pull out and may survive better even if large sections are cut off.

This is the best of two worlds: a long compounding trajectory and simultaneously lower idiosyncratic risk, hence a growing tree with an increasingly sprawling root system.

After spending time on high-performing conglomerates, you realize how naive we are as shareholders in individual companies, underwriting single-exposure risks like product concentration, customer concentration risk, key personnel risk, regulatory risk, financial risk, extreme cyclicality, or relying on a single end-market. Any of these risks will eventually play out in the fullness of time. However, isn’t that what portfolio construction is meant for? Size accordingly. With this internal diversification, owning fewer than five serial acquirers could mean that you`re more diversified than a portfolio of more than five single-exposure companies. This framework on optimizing resilience and optionality, laid out by NZS Capital, might be relevant in this context.

In terms of examples, look no further than the organization chart of Constellation Software which perfectly illustrates a sprawling root system (6 operating groups across 100+ verticals and 1000+ underlying businesses, including Topicus, which is spun off, click on image for zoom).

And similarly, Lifco, one of the great generalist acquirers from Sweden with around 180+ underlying companies across multiple niches and geographies (h/t REQ Capital):

I also find generalists and theme-based specialists that have successfully expanded their M&A capabilities globally over many years to be in a better position, building repetition and datasets, resulting in additional derisking and TAM growth. Case in point, a Nordic generalist like Lifco or Lagercrantz might have considerably more scaling opportunities and lower risk compared to Nordic peers who are often constrained within specific countries in the region. Building up these capabilities, spanning multiple borders and cultures, take time and skill and is hard to pull off in a decentralized machine.

Speaking of repetition and datasets, the following summary from MBI Deep Dives gives a good overview of the data-driven acquisition process and diligence present at Constellation Software:

The board and/or headquarter (HQ) recommends and sets hurdle rates for acquisition -> HQ creates a threshold for acquisition for OGs (operating groups) for which they won’t be required to ask for approval from HQ/board (similarly, the OGs can have similar threshold for BU managers (BU = business units)-> the M&A/business development team or the deal sourcing manager calculates potential IRR for the deal and creates bull/base/bear case scenarios for each acquisition to see where exactly their base case scenarios fall in distribution based on historical acquisition track record (is it 55th percentile or 95th percentile; the manager better has VERY high confidence if their projections appear to be 95th percentile)-> one year after the acquisition, there is Post Acquisition Review (PAR) in which the manager/team discusses the initial projections and actual result as well as the lessons from the experience-> BUs try to use cash to acquire more companies and if they don’t see much opportunity, they can repatriate cash to HQ. But if a BU consistently generates high IRR and wants to repatriate money to HQ, HQ may ask the BU to “Keep Your Capital” (KYC) so that BUs are more incentivized for deploying capital at lower IRRs (but higher than hurdle rates). On the other hand, if an acquisition does poorly, it remains in your capital base while calculating your ROIC. You cannot “adjust” your capital for impairment later which also acts as an incentive to allocate capital prudently.

All (Good) Investing is Sidecar Investing

Sidecar investing was first introduced to me by Richard J. Zeckhauser in his paper “Investing in the Unknown and Unknowable.” The analogy can be described as follows:

The investor rides along in a sidecar pulled by a powerful motorcycle. The more the investor is distinctively positioned to have confidence in the driver’s integrity and his motorcycle’s capabilities, the more attractive the investment.

Sidecar investing essentially means placing your bet on the management, who themselves are great investors, and you are holding on for the ride – hence the sidecar! In other words, a rare species that combines the best of both worlds: management teams that are excellent operators and fantastic investors.

There’s also a significant element of trust involved – after all, you`re sitting in a sidecar, remember? Trust and culture are one of those intangibles which can`t be neatly siloed or excel-ranked. However, you should not bet on a single jockey, hoping they will never leave the company. You should look for a company with an everlasting and celebrated culture around value creation (yes, easier said than done).

Notice that there`s something deeper going on here; it’s a virtuous cycle; the management is doing the work for you, and you are piggybacking their ability to compound capital and adapt to changes in the environment. This frees up time for you as an investor, where you don’t need to find new investment ideas every month, increasing your focus and the quality of your thoughts.

But don’t we constantly, as minority shareholders, invest in public companies and ride along in a sidecar, trusting management to be both good operators and great investors? If you manage other people’s money, you probably have limited partners who have underwritten your ability to compound their capital, so why is this any different? This also begs the question:

If a minority of investors can beat the market by investing intelligently, why can’t a minority of managers create value by acquiring intelligently? – Pat Dorsey

Parts of the investing community may have issues with sidecar investing. After all, what are portfolio managers paid for? Media headlines some time ago on funds charging fees for all-in positions in Berkshire Hathaway come to mind. Perhaps there is some merit to this, but investors should remember that their scorecard is not computed using Olympic-diving methods: degree of difficulty does not count (as the saying goes). Besides the analytical framework for sourcing and identifying these companies, let us not forget that the destination matters, hence staying the course and reaping the full benefits of business compounding.

Positive Skewness

Some may look at acquirers from a surface level and attribute historical performance solely in terms of multiple arbitrage. Buy companies at low multiples, integrate successfully, and the market will apply the acquirer’s multiple to a bigger earnings base. This is only partly explaining the story, though. Smaller private deals should rightfully be discounted compared to a public company offering scale, diversification, and liquidity. Moreover, the inverse of the multiple paid can also be used to arrive at the return on incremental capital without considering organic uplift. So, I think the multiple arbitrage argument deserves more context in a universe of IRR-focused capital allocators.

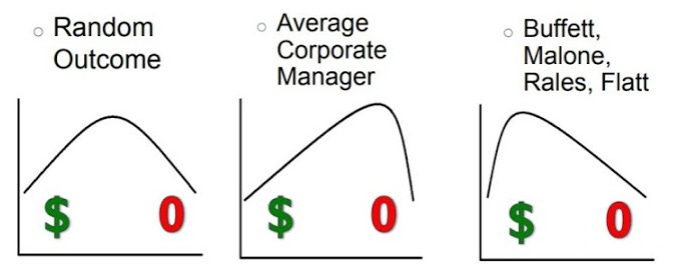

Additionally, it is worth pondering over why the sidecar opportunity in serial acquirers “exists” and what variant perceptions this area represents. Skilled capital allocation (or investing) could be described as having the following attributes:

A focus on the end destination, not the path.

Unpredictable - hard for the sell-side to model (although more sell-siders try!)

Unconventional - Creating value via acquisitions when most companies destroy value

Lumpy - Value creation is financially messy and comes in spurts rather than a smooth line.

A big source of variant perception is represented by the fact that growth for these companies is a function of “ebb and flow.” Some of it is organic and some inorganic, with the latter being highly unpredictable, both in timing and size. In other words, this group of companies does not lend itself particularly well to the agenda of the sell-side, trying to pinpoint a 12-month price target. Remember that these companies, for the most part, don`t provide any guidance (and rightly so), and the great ones don’t raise equity (self-funded).

Move Along, Nothing to See Here!

Investors new to serial acquirers, looking for optical cheapness, gravitational pull towards “valuation” heuristics like <10x next year’s earnings = cheap, 10-15x = ok, and >15x = expensive, may easily ignore this segment of the market. It’s easy but perhaps intellectually lazy to assume you are “late to the party.” Still, multiples can sometimes mislead, and the most important job is figuring out how much capital can be reinvested and at what returns for how long. Too often, though, the “how long” part tends to receive the least attention, even though intrinsic value grows exponentially with time when return hurdles are met.

As per Mark Leonard from Constellation Software:

An exceptional case of value investing is the example of a company that is growing quickly, that the market expects to stop growing within the next 5-7 years, but that keeps growing quickly for much longer. If you can spot one of those, it may appear expensive on a P/E basis, but may actually be an attractive long-term investment on a “value investing” basis. Spotting this kind of investment requires the ability to foretell the distant future…which is extremely difficult to do with consistency.

Value Creation is Messy

It’s worth pointing out that we`re participating on a different time scale as sidecars investors. Welcome to the business time scale, where value creation comes in spurts rather than a smooth line and where the path to riches doesn’t correlate perfectly with the incentives of the marginal price setter.

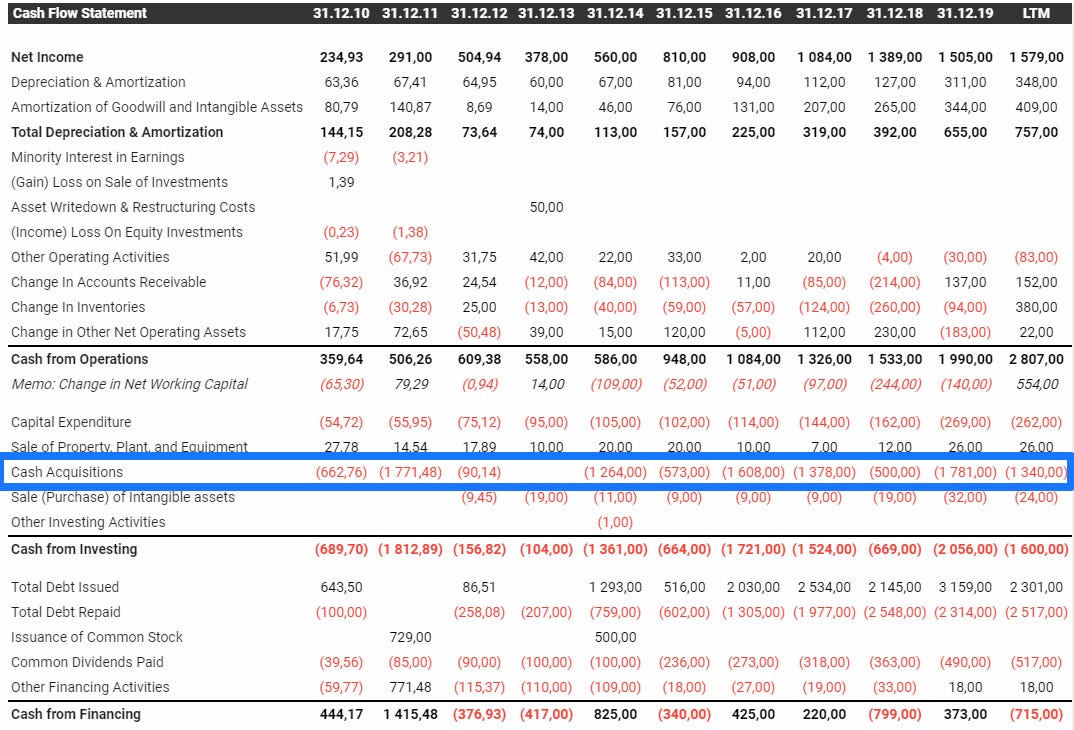

Case in point from Swedish Lifco (a generalist acquirer): how can you intelligently incorporate these lumpy acquisitions into a DCF model? For the record, ROIC has averaged >20%, including goodwill.

This is the outskirt of the time spectrum, where earnings guidance is futile and where the end destination is what matters, not the path. However, you should still be keenly aware of any data points signaling the degree of management execution, culture drift, and the quality of the compounding trajectory. Stay in the sidecar (but don`t fall asleep!)

Escaping Base Rates

The playbook for most finance alumni is to think everything in finance has mean-reverting attributes. Heck, the original framework for value investing was partly based on mean-reversion. Why should one expect, as a default, that a company with a reinforcing culture around the business building and positively skewed capital allocation will mean-revert in terminal year 5? Why not focus on the exception from the rule?

If you can identify the minority of managers highly skilled at capital allocation, you should probably apply a different lens to the compounding trajectory. This is where creativity, trust and underwriting of the unknown and unknowable come into full play, perhaps four words shunned or scuffed at in certain value circles, but bear with me. We enter a domain where intuitive thinking and deeply ingrained mental models must be questioned, paused, or abandoned. This time you need to put yourself in a position to reap the full benefits of long-term value creation.

Another benefit of being a sidecar investor is that you can finally thrive in market drawdowns, despite running a fully invested portfolio where the underlying companies have some flexibility. Lower prices could mean more optionality, hence more opportunities for intrinsic value growth. This could take the form of market share growing organically or via compelling acquisitions or perhaps share repurchases at attractive prices. If you zoom out, it is mind-boggling to witness how much intrinsic value growth can be generated by exceptional people, compounding good decisions, over long periods.

The Opportunity

The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is now. - Chinese Proverb

I think there is a tendency in the value-investing community to overdose on the usual suspects from the book “The Outsiders” by William Thorndike. That covers Berkshire Hathaway, Constellation Software, Fairfax, Teledyne, TCI, et al. Fantastic capital allocators. Still, we can all agree the best would be to track every successful company ahead of time when the companies were small. Realistically, however, there is a trade-off between track record and the size and length of the growth runway. What ultimately matters, from a new perspective, in the future and how much capital these companies can deploy, at what rates, and for how long.

In terms of acquirers specifically, it’s also worth highlighting that the 20-year tailwinlow-interesterest rates have lifted all boats relying on external financing to fund their acquisitions. Interest rates and multiples are also linked. In other words, the future may not duplicate the past for some of these companies.

Let’s buckle up!

Recommended readings:

Studying Serial Acquirers (very good on the importance of scaling deal volume vs. deal size)

Mark Leonard’s shareholder letters

Investing in the Unknown and Unknowable

How lots of small M&A deals add up to big value

Practice Makes Perfect: What sets programmatic acquirers apart

Learnings from Swedish Serial Acquirers

In Practice (lots of great interviews and resources on serial acquirers)

Chapter three, “Deflated Roll-ups” from the book “Billion Dollar Lessons.”

Brent Beshore interviews with Patrick Oshag: here and here (side note: I first listened to the interview back in 2017 where Beshore is talking about private deals at extremely low single-digit multiples for good businesses, which was very intriguing (although often optical cheap for great reasons), but little did I know we had a universe of public equivalents, doing this at scale, in my backyard (Sweden)

Company-specific case studies:

Addtech: Acquirers.com

Constellation Software: The 10th Man | MBI Deep Dive

Diploma: Coloussus

Halma: Chris Mayer’s blog

Heico: Analyzing Good Businesses

Instalco: Exploring Context

Kelly Partners Group: Acquirers.com

Lifco: The Equity Ideas

Roper Technologies: Analyzing Good Businesses

Teqnion: Acquirers.com

Topicus: The 10th Man

TransDigm: 50X Podcast

Vitec Software: Global Quality Investing

For more Addtech, Addlife, Halma, Lifco, Judges Scientific, more CSU, TOI, etc: In Practice